Introduction

This final portion of Isaiah is essential because many Christians assume that the coming of Christ in Matthew 24:30-31, 1 Thessalonians 4:15–17 and 2 Peter 3 describes the end of the physical world . But like Isaiah 65–66, Jesus and Paul use symbolic, apocalyptic language. Both point to the end of the old covenant world and the arrival of the new Jerusalem—fulfilled in AD 70—not the destruction of the planet.

Isaiah 63 builds on the themes of the preceding chapters. The Messiah is depicted as a warrior-judge, bringing vengeance on His enemies and salvation to His remnant, echoing Jubilee themes (vv. 1–6). The chapter then recalls God’s redemptive acts in the first exodus (vv. 7–19).

Isaiah 64 pleads for God to “rend the heavens and come down” as He did at Sinai. Isaiah 51 and sources like The New Treasury of Scripture Knowledge interpret such language as symbolic of covenant formation—God establishing Israel as a “heaven and earth.”[1] If God’s first coming wasn’t visible or global, why assume the second must be?

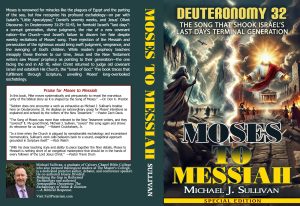

This sets the stage for Isaiah 65–66, where God forms a new “nation,” “Jerusalem,” and “heavens and earth” in response to Israel’s covenant failure. The imagery builds directly on Moses’ prophecy in Deuteronomy 32: Israel’s end would come in fire and judgment, provoking God to raise up a “foolish nation” in her place (Deut. 32:20–21).

The New Covenant Nation / Jerusalem / Heavens and Earth

In Deuteronomy 32, Moses uses apocalyptic language to describe Israel’s judgment as the destruction of her covenantal world—her religious and political order. Isaiah and the New Testament writers continue this imagery, depicting Jerusalem’s destruction in AD 70 as the prophesied “end” of the old covenant order. Isaiah 65–66 builds on this, foretelling a new creation—the Church—as the new Jerusalem, rising from the ruins of the old.

John Lightfoot affirms that this de-creation refers to Jerusalem’s judgment in AD 70:

“The destruction of Jerusalem is very frequently expressed in Scripture as if it were the destruction of the whole world … ‘A fire is kindled in mine anger, and shall burn unto the lowest hell … and shall consume the earth with her increase, and set on fire the foundations of the mountains.’ (Deut. 32:22)”[2]

Adam Clarke agrees:

“Deuteronomy 32:22. The lowest hell — שאול תחתית sheol tachtith, the very deepest destruction; a total extermination, so that the earth – their land, and its increase, and all their property, should be seized; and the foundations of their mountains – their strongest fortresses, should be razed to the ground. All this was fulfilled in a most remarkable manner in the last destruction of Jerusalem by the Romans, so that of the fortifications of that city not one stone was left on another. See the notes on Matthew 24:1–51.”[3]

This vivid portrayal of ruin sets the stage for Gill’s interpretation, which ties the fiery imagery directly to the historical burning of Jerusalem and its temple:

For a fire is kindled in mine anger… Here begins the account of temporal and corporeal judgments inflicted on the Jews for their disbelief and rejection of the Messiah… this here respects the destruction of the land of Judea in general, and the burning of the city and temple of Jerusalem in particular… and shall consume the earth with her increase: the land of Judea, with the cities and towns in it… all were destroyed and consumed at or before the destruction of Jerusalem… and set on fire the foundations of the mountains; the city of Jerusalem, as Jarchi himself interprets it… and the temple of Jerusalem particularly was built on Mount Moriah, and that as well as the city was utterly consumed by fire…[4]

Ernest L. Martin adds that Jerusalem, like Rome, was known as the “City of Seven Hills”:

..the City of Jerusalem as it existed in the time of Christ Jesus was also reckoned to be the “City of Seven Hills.” This fact was well recognized in Jewish circles… the writer [of Pirke de Rabbi Eliezer] mentioned without commentary… that Jerusalem is situated on seven hills” (recorded in The Book of Legends, ed. Bialik and Ravnitzky, p. 371).[5]

Martin identifies these seven hills as follows: Scopus [Hill One], Nob [Hill Two], “Mount of Corruption” or “Mount of Offense” (2 Kings 23:13) [Hill Three], the original “Mount Zion” [Hill Four], “Ophel Mount” [Hill Five], “Fort Antonia,” built on the “Rock” [Hill Six], and the southwest hill, the new “Mount Zion” [Hill Seven].

Jerusalem, like a diamond nestled among its seven hills, would face a judgment so severe that it would consume the city and reach these surrounding hills. This foretells Israel’s old covenant de-creation and her “end” in AD 70.

The contexts of Deuteronomy 32 and Isaiah 65–66 are almost identical. In Deuteronomy 31–32, Israel rejects her Messiah, the “Rock,” in her last days, amasses bloodguilt, and provokes covenantal judgment(Deut. 31:29; 32:20–43). Isaiah describes the same pattern: Israel again fills up the measure of her sins, and God responds in kind:

“‘I will not keep silent, but I will repay … both your iniquities and your fathers’ … I will measure into their lap payment for their former deeds’” (Isa. 65:6–7).

As seen in Isaiah 2–3, the unfaithful face slaughter and the sword, while a faithful remnant is preserved (Isa. 65:8–16; cf. Deut. 28).

To modern readers, the creation of a “new heavens and new earth” might sound like the end the literal heavens and earth. But to ancient Jewish audiences, this was standard prophetic language symbolizing covenantal transition. The Hebrew word erets, often translated as “earth,” is better rendered as “land” in this context, pointing to Jerusalem’s historical judgment. The context is clearly pre-AD 70: Israel is still under the Mosaic covenant and facing judgment for violating it. Survivors remain, which further confirms this is not the end of the planet.

Many assume Isaiah 65–66 describes a future cosmic event, but the passage itself suggests otherwise:

“Look! I am about to create new heavens and a new earth … I am about to create Jerusalem as a source of rejoicing … There will no longer be a nursing infant who lives only a few days, or an old man who does not fill his days … they shall build houses and inhabit them … The wolf and the lamb shall feed like one … They shall do no evil … on all my holy mountain,” says Yahweh (Isa. 65:17–25, LEB, italics original).

This new creation describes a renewed covenant people—living, laboring, giving birth, and worshiping in peace—not a post-apocalyptic world, but the Church born out of judgment and restoration.

Examine the immediate and previous context of Isaiah 65:1–16: because old covenant Israel, a “rebellious people,” had once again broken the old covenant, God declares He will form a new nation from the faithful Jewish remnant and the Gentiles. This mirrors the pattern in Deuteronomy 32 and Isaiah 24, where Israel’s covenant violation leads to de-creation judgment. In Isaiah 65:3–4, Israel is seen sacrificing to fertility gods, consulting the dead, and eating unclean food—clear transgressions of the Law.

But how could these covenant violations occur in a post-AD 70 context, if, as many futurists argue, the Law of Moses was already fulfilled or abolished at the cross?

A literal reading that places this prophecy at the end of world history also faces internal inconsistencies: Isaiah describes childbirth (v. 20), physical death (v. 20), ongoing sin (v. 20), and ordinary labor (vv. 21–22) within the new heavens and new earth. A strict literalist view must account for these details.

Isaiah 24 confirms this interpretation. It links Israel’s covenant violations to the desolation of “the city” and its land—Jerusalem—not a global apocalypse. In Isaiah 65:12, God brings the “sword” of a foreign nation (Rome), marking the destruction of the old covenant order.

As Doug Wilson rightly observes, Isaiah 65–66 is not about the end of world history, but about covenantal transition:

“We are seeing here the transition between the first heaven (the Judaic aeon) and new earth (the Christian aeon).…I do not take the new heaven and new earth as referring to the…eternal state… I take the first heavens and earth as the Judaic aeon and the new heavens and earth as the Christian aeon… the former ending with the destruction of the temple in 70 A.D”[6]

This is the position of great theologians such as John Lightfoot, John Owen, Gary DeMar, James Jordan, Peter Leithart, R.C. Sproul, and many more.

Consider John Owen’s treatment of 2 Peter 3. He argues that the first “heavens and earth” represent the old covenant order, while the “new heavens and earth” signify the new covenant inaugurated by the gospel. Owen distinguishes between two covenantal worlds—one destroyed by water, the other by fire:

“That the apostle makes a distribution of the word into heaven and earth, and saith, they were destroyed with water… the heavens and earth that were then, and were destroyed by water, [are] distinct from the heavens and the earth that were now, and were to be consumed by fire; and yet, as to the visible fabric… they were the same… and continue so to this day; when yet it is certain that the heavens and earth whereof he speaks were to be destroyed and consumed by fire in that generation.”[7]

Owen’s point is clear: Peter does not refer to the physical cosmos being annihilated—either in Noah’s day or in the first century. The material world remained intact. What perished was the covenantal world of people, priesthood, and polity.

Likewise, the “heavens and earth” Peter speaks of in his own time refers not to the literal universe, but to the Mosaic system—about to be judged and replaced. Just as the flood ended the antediluvian order, the fire of AD 70 would bring the final end of the old covenant age and the full unveiling of the new covenant “heavens and earth.”

Owen then explains that Scripture often uses “heavens and earth” symbolically, referring to civil and religious systems rather than the physical universe:

It is evident, then, that in the prophetical idiom… by ‘heavens’ and ‘earth,’ the civil and religious state and combination of men… are often understood. So were the heavens and earth that world which was then destroyed by the flood.[8]

In other words, the “heavens” symbolize rulers or spiritual authorities, and the “earth” the people governed. The flood didn’t destroy the planet, but the covenantal world of that generation. This apocalyptic idiom appears throughout the Old Testament—for example, in Isaiah 13:10 (Babylon) and Isaiah 34:4 (Edom). Likewise, Peter’s “heavens and earth” (2 Pet. 3) refers to the Jewish world—its temple, priesthood, and national identity—on the brink of fiery judgment in AD 70.

Finally, Owen ties Peter’s prophecy directly to Isaiah’s promise of a “new heavens and earth,” showing that it refers to the establishment of the gospel era:

Now it is evident… that this is a prophecy of gospel times ONLY; and that the planting of these new heavens is NOTHING BUT the creation of gospel ordinances, to endure forever. The same thing is so expressed, Heb. xii. 26–28.

He concludes with a powerful exhortation:

Seeing that… all these things, … shall be dissolved… in a way of judgment, wrath, and vengeance, by fire and sword… let others mock at the threats of Christ’s coming. – he will come, he will not tarry; and then the heavens and earth that God himself planted—the sun, moon, and stars of the Judaical polity and church—the whole old world of worship and worshippers…. shall be sensibly dissolved and destroyed. This… shall be the end of these things, and that shortly.[9]

In Owen’s view, Peter’s fiery “end” is not about planetary destruction but the dramatic dissolution of the Judaic covenantal world. The “new heavens and earth” signify the enduring gospel kingdom—a spiritual cosmos created through Christ (cf. Heb. 12:26–28).

The sun, moon, and stars of Israel’s world (symbols of its national and religious order) would be darkened and fall, just as Jesus foretold in Matthew 24:29–34. He explicitly placed this cosmic judgment within His generation, signaling the swift and final end of the old covenant age and the inauguration of the new.

The influential exegete John Lightfoot agreed, insisting that the “elements” passing away in 2 Peter 3 ’s referred not to the physical universe, but to the Mosaic system:

That the destruction of Jerusalem is very frequently expressed in Scripture as if it were the destruction of the whole world, Deut. xxxii. 22; ‘A fire is kindled in mine anger… and shall consume the earth with her increase, and set on fire the foundations of the mountains’ Jer. iv. 23; ‘I beheld the earth, and lo, it was without form and void; and the heavens, and they had no light; The discourse there also is concerning the destruction of that nation.[10]

Deuteronomy 32 and Jeremiah 4, Lightfoot observes, use cosmic destruction language to describe judgment upon Israel, not the end of the physical universe. The darkening of the heavens and the shaking of the earth are covenantal symbols representing national upheaval and divine judgment.

Lightfoot then explains that after the destruction of Jerusalem, the Bible speaks of a “new heavens and a new earth”—not as a new physical cosmos, but as the inauguration of the new covenant era:

With the same reference it is, that the times and state of things immediately following the destruction of Jerusalem are called ‘a new creation,’ ‘new heavens,’ and ‘a new earth,’ Isa. lxv. 17… you will find the Jews rejected and cut off; and from that time is that new creation of the evangelical world among the Gentiles.[11]

For Lightfoot, Isaiah 65 describes not the end of world history, but the end of the Mosaic system and the rise of the gospel age. Paul and John affirm this in 2 Corinthians 5:17 and Revelation 21:1–2, where the “new creation” refers to the Church established through Christ.

Lightfoot applies the same lens to 2 Peter 3:

“‘We, according to his promise, look for new heavens and a new earth’ The heavens and the earth of the Jewish church and commonwealth must be all on fire… but we… look for the new creation of the evangelical state.”[12]

He interprets Peter’s language about the “elements melting with fervent heat” as a metaphor for the abolition of Mosaic structures—not the destruction of the universe:

“Compare this with Deut. xxxii. 22, Heb. xii. 26: and observe that by elements are understood the Mosaic elements, Gal. iv. 9, Coloss. ii. 20: and you will not doubt that St. Peter speaks ONLY of the conflagration of Jerusalem, the destruction of the nation, and the abolishing the dispensation of Moses.”[13]

By citing Galatians 4:9 and Colossians 2:20, Lightfoot underscores that Peter’s “elements” were the old covenant laws, now obsolete. Their “burning” symbolized God’s judgment on Israel and the final removal of the old order.

By citing Galatians 4:9 and Colossians 2:20, Lightfoot underscores that Peter’s “elements” were the old covenant laws, now obsolete. Their “burning” symbolized God’s judgment on Israel and the final removal of the old order.

Together, Lightfoot and John Owen maintain that 2 Peter 3’s cosmic imagery reflects covenantal transformation, not planetary destruction. The “new heavens and new earth” represent the arrival of the gospel age—the fulfillment of Isaiah’s promise and the hope of the New Testament Church.

The NEW Heaven and Earth

The Greek word for “new” in 2 Peter 3:13 is kainos, meaning new in kind or quality—not neos, which indicates newness in time. This distinction reinforces that the “new heavens and new earth” reflect a transformed covenantal order, not a newly created physical universe. They correspond to Daniel’s prophecy of the “stone cut without hands,” a spiritual and eternal kingdom fundamentally different from all others.

The old covenant had to pass away to make room for the mature form of the new covenant, which reached its fulfillment in AD 70. This transformation ushered in a new covenant heavens and earth that includes a spiritual land, city, temple, priesthood and sacrifices—forming the foundation of God’s renewed creation.

The symbolic de-creation language in Deuteronomy 32:22 powerfully depicts Israel’s covenantal judgment. This theme is echoed in 2 Peter 3 and Isaiah 65–66, where prophetic imagery signals not global catastrophe but a decisive covenantal transition. Peter’s allusion to Isaiah’s new creation points to the replacement of the Mosaic order with the new covenant era.

While some may challenge a first-century fulfillment of these prophetic texts, the consistent scriptural patterns and historical context affirm that this transition was both imminent and realized within the apostolic generation. The de-creation of old covenant Israel serves as a stark reminder of God’s faithfulness to His covenant and His justice in responding to rebellion.

Isaiah’s vision of judgment leads directly into hope. The destruction of the old was not the end of redemption—it was the beginning of the new. As we continue, we will explore how Israel’s sins—especially the shedding of innocent blood—were “stored up” for judgment, further underscoring God’s retributive justice and covenantal fidelity.

Jesus, Paul, and Isaiah 63–66

Both Moses and Isaiah prophesy that a new covenant “nation” would arise as old covenant Israel reached her end. Jesus affirms this pivotal transition:

“Therefore, I tell you, the kingdom of God will be taken away from you [national old covenant Israel/Jews] and given to a nation/people producing its fruits” (Matt. 21:43).

Earlier in Matthew’s gospel, Jesus warned that the “sons of the kingdom” [old covenant Jews] would be cast into “outer darkness,” while Gentiles from “east and west” would enter the kingdom (Matt. 8:10-12). Both passages anticipate the AD 70 fulfillment of the old covenant promises, when the typological nation gives way to the spiritual kingdom realized in Christ and His Church. As Jacob prophesied, in Israel’s “last days,” the “scepter” would depart from Judah and pass to Messiah (Gen. 49:10). This authority now belongs to Christ and His church—the new covenant “nation”—where rule is exercised through the gospel.

Jesus also applied the apocalyptic language of His time to this covenantal shift:

“Immediately after the tribulation of those days the sun will be darkened, and the moon will not give its light, and the stars will fall from heaven, and the powers of the heavens will be shaken” (Matt. 24:29).

“Truly, I say to you, this generation will not pass away until all these things take place. Heaven and earth will pass away, but my words will not pass away” (Matt. 24:34–35).

Many modern Evangelicals overlook that, for centuries, both older and contemporary commentators have understood Matthew 24 (and its parallels in Mark 13 and Luke 21) as apocalyptic symbolism fulfilled in AD 70. John Bray, in Matthew 24 Fulfilled, catalogs numerous voices affirming this interpretation.

For example, Bray quotes N. Nisbett on the symbolic nature of de-creation in Matthew 24:29:

[T]his language was borrowed from the ancient hieroglyphics: for as in hieroglyphic writing, the sun, moon, and stars were used to represent states and empires, kings, queens, and nobility; their eclipse and extinction, temporary disasters or overthrow… the holy prophets call kings and empires by names of the heavenly luminaries; their misfortunes and overthrow are represented by eclipses and extinction; stars falling… denote the destruction of the nobility… (Warburton’s Divine Legation, vol. 2, book 4, section 4, quoted by N. Nisbett, Our Lord’s Prophecies of the Destruction of Jerusalem, 22–23).[14]

Adam Clarke, commenting on the apocalyptic language in Isaiah 13:9–10 and Ezekiel 32:7–8, writes: “The destruction of the Jews by Antiochus Epiphanes is represented by casting down some of the host of heaven, and the stars to the ground. See Dan. Viii. 10. And this very destruction of Jerusalem is represented by the Prophet Joel, chap ii. 30, 31 by showing wonders in heaven and in earth—darkening the sun, and turning the moon into blood. This general mode of describing these judgments leaves no room to doubt the propriety of its application in the present case).”[15]

As noted, the context of Matthew 23–24 centers on the fall of Jerusalem and the destruction of the temple. The sun, moon, and stars symbolized Israel’s covenantal world—her religious and civil authorities—who would lose their covenantal status by AD 70 for rejecting Christ, His apostles, and His prophets (cf. Matt. 23:31–36).

Reformed and Puritan theologian John Owen likewise explains the symbolic nature of this de-creation language in Matthew 24:29:

When mention is made of the destruction of a state and government, it is in that language that seems to set forth the end of the world… Isa. 34:4… is yet but the destruction of the state of Edom. And our Saviour Christ’s prediction of the destruction of Jerusalem… he sets it out by expressions of the same importance… by ‘heavens’ and ‘earth’, the civil and religious state and combination of men in the world… are often understood.[16]

John L. Bray also notes: “Jewish writers understood the light to mean the law; the moon, the Sanhedrin; and the stars, the Rabbis.”[17]

Thus far, contextual and grammatical analysis suggests that the “end of the age” in verse 3 refers to the end of the old covenant age, while the stars falling from the heavens in verse 29 signify the downfall of religious and civil authorities. But what of Matthew 24:35, which states “heaven and earth will pass away”? Could this truly mean the end of the physical world?

Heaven and Earth as Temple Symbolism

A closer look through a contextual, grammatical, and historical lens within the Christian tradition reveals that such language may also apply to the old covenant “heavens and earth” and its temple.

Though not a Preterist, G.K. Beale argues that in the OT, “‘heaven and earth’… may sometimes be a way of referring to Jerusalem or its temple, for which ‘Jerusalem’ is a metonymy.”[18]

Evangelical scholar Crispin H.T. Fletcher-Louis makes similar observations about the passing of “heaven and earth” in Mark 13:31 and Matthew 24:35, viewing it as a symbol for the old covenant system embodied in the temple: “The temple was far more than the point at which heaven and earth met. Rather, it was thought to correspond to, represent, or, in some sense, to be ‘heaven and earth’ in its totality. . . [T]he principal reference of ‘heaven and earth’ is the temple-centered cosmology of second-temple Judaism which included the belief that the temple is heaven and earth in microcosm. Mark 13[:31 or Matthew 24:35 and Matthew 5:18 refer then to the destruction of the temple as a passing away of an old cosmology.”[19]

Indeed, the temple was conceived as a reflection of heaven and earth itself, with the Tabernacle mirroring the days of creation:

| Day | Creation | Tabernacle |

| Day 1 | Heavens are stretched out like a curtain (Ps. 104:2) | Tent (Exod.26:7) |

| Day 2 | Firmament (Gen. 1:2) | Temple veil (Exod.26:33) |

| Day 3 | Waters below firmament | Laver or bronze sea (Exod. 30:18) |

| Day 4 | Lights (Gen.1:14) | Light stand (Exod. 25:31) |

| Day 5 | Birds (Gen. 1:20) | Winged cherubim (Exod. 25:20) |

| Day 6 | Man (Gen. 1:27) | Aaron the high priest (Exod. 28:1) |

| Day 7 | Cessation (Gen. 2:1)

Blessing (Gen. 2:3) Completion (Gen.2:2) |

Cessation (Exod. 39:32)

Mosaic blessing (Exod. 39:43) Completion (Exod. 39:43)[20] |

Let’s now turn our attention to the second de-creation passage mentioned by our Lord:

“Do not think that I have come to abolish the Law or the Prophets; I have not come to abolish them but to fulfill them. For truly, I say to you, until heaven and earth pass away, not an iota, not a dot, will pass from the Law until all is accomplished” (Matt. 5:17–18).

Reformed theologian John Brown recognized the symbolic use of this language, writing:

“But a person at all familiar with the phraseology of the Old Testament Scriptures, knows that the dissolution of the Mosaic economy, and the establishment of the Christian, is often spoken of as the removing of the old earth and heavens, and the creation of a new earth and new heavens.”[21]

Commentators are correct to identify the “heaven and earth” in Matthew 5:18 with that of Matthew 24:35. But in both cases, the context points to the end of the old covenant order—not the end of the physical cosmos. According to Jesus, if “heaven and earth”—and all OT prophecy—have not yet passed away (or been fulfilled), then every “jot and tittle” of the Mosaic Law would still bind us.

Jesus maintains consistency in His teaching. Matthew 5:17–18 aligns with Matthew 24:29, 35 and Luke 21:22–32, where He places the fulfillment of “all that has been written” firmly within His generation.

Neither Jesus nor any New Testament writer predicted the end of the physical planet or world history in Matthew 24:3, 29, 35 or similar NT passages.. A closer look at the works of leading Reformed and evangelical scholars reveals that nearly every “de-creation” prophecy in Scripture is best understood in covenantal, not cosmic, terms.

Scholars including John Owen, John Locke, John Lightfoot, John Brown, R.C. Sproul, Gary DeMar, Kenneth Gentry, James Jordan, Peter Leithart, Keith Mathison, Crispin H.T. Fletcher-Louis, Hank Hanegraaff, and N.T. Wright (to name just a few) interpret the passing away of “heaven and earth” (cf. Matt. 5:17–18; 24:3, 29, 35; 1 Cor. 7:31; II Peter 3; I John 2:17–18; Rev. 21:1) as referring to the destruction of the temple or the civil and religious worlds of men—Jewish or Gentile. They argue that the rulers of the old covenant system or world, along with the temple, were symbolized by the “sun, moon, and stars” of the “heaven and earth” that perished in AD 70. See the following works:

- John Owen, The Works of John Owen, 16 vols. (London: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1965–68), 9:134–135.

- John Lightfoot, Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica: Matthew – 1 Corinthians, 4 vols. (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson Publishers, [1859], 1989), 3:452, 454.

- John Brown, Discourses and Sayings of our Lord, 3 vols. (Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, [1852] 1990), 1:170.

- John Locke, The Clarendon Edition of the Works of John Locke: A Paraphrase and Notes on the Epistles of St Paul Volume 2, (NY: Oxford University Press, 1987), 617–618.

- C. Sproul, The Last Days According to Jesus (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Books, 1998).

- Kenneth Gentry, He Shall Have Dominion (Tyler TX: Institute for Christian Economics, 1992), 363–365. Kenneth Gentry (contributing author), Four Views on the Book of Revelation (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Zondervan, 1998), 89.

- Gary DeMar, Last Days Madness: Obsession of the Modern Church (Powder Springs: GA, 1999), 68–74, 141–154, 191–192.

- James B. Jordan, Through New Eyes Developing a Biblical View of the World (Brentwood, TN: Wolgemuth & Hyatt, Publishers, 1998), 269–279.

- Crispin H.T. Fletcher-Louis (contributing author) Eschatology in Bible & Theology (Downers Grove, Illinois: Inter Varsity Press, 1997), 145–169.

- Peter J. Leithart, The Promise of His Appearing: An Exposition of Second Peter (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2004).

- Keith A. Mathison, Postmillennialism: An Eschatology of Hope (Phillipsburg, NJ: P&R Publishing, 1999), 114, 157–158.

- T. Wright, Jesus and the Victory of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 1996), 345–346.

- T. Wright, The Resurrection of the Son of God (Minneapolis, MN: Fortress Press, 2003), 645, n.42.

- Hank Hanegraaff, The Apocalypse Code (Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 2007), 84–86.

While these interpretations are individually considered “orthodox,” full preterists synthesize them into a cohesive biblical theology: the Bible is not about the end of world history, but rather the end of a covenant world—and the beginning of another. The de-creation of old covenant Israel marked the transition to the new covenant “heavens and earth” established in Christ.

Paul and the New Creation in Isaiah

While Paul does not address the formation of God’s new covenant “nation” or the eschatological de-creation of old covenant Israel directly in 1–2 Thessalonians, he does elsewhere—explicitly quoting from Isaiah 63–66. In Romans, after showing that the gospel had been preached throughout the Roman world (fulfilling Jesus’ sign that “the end” was near, Matt. 24:14), Paul calls Moses and Isaiah as witnesses to God’s plan to replace old covenant Israel:

“But I ask, have they not heard? Indeed, they have, for ‘Their voice has gone out to all the earth’ … But I ask, did Israel not understand? First Moses says, ‘I will make you jealous of those who are not a nation … Then Isaiah is so bold as to say, ‘I have been found by those who did not seek me; I have shown myself to those who did not ask for me’” (Rom. 10:18–20).

In citing Deuteronomy 32 and Isaiah 65–66, Paul affirms that Torah foresaw Israel’s “end” and the rise of a new covenant nation. For Paul, true Israel is not defined ethnically but covenantally—the believing remnant and Gentile believers together form restored Israel at Christ’s coming (Rom. 9:6; 11:25–27; 13:11–12).

Though Paul may not cite Isaiah 65–66 as directly as Peter (2 Pet. 3) or John (Rev. 21–22), he clearly refers to the same timeframe. In 1 Corinthians, Paul tells the church: “the appointed time has grown very short” and “the present form of this world is passing away” (1 Cor. 7:29, 31).

This matches Isaiah 60:22 (LXX): “In the appointed time [kairos] I will bring it about quickly.” Peter likewise uses the present tense: the heavens and earth (of Isaiah 65–66) are “being destroyed” (2 Pet. 3:10–11, LEB), indicating a transition already underway in the first century.

Paul Paul directly connects Isaiah 65 to the new creation when he writes: “Therefore, if anyone is in Christ, he is a new creation. The old has passed away; behold, the new has come (2 Cor. 5:17). This echoes Isaiah 65:17: : “For behold, I create new heavens and a new earth, and the former things shall not be remembered or come into mind. In context, Paul is clearly teaching the Corinthian church that the old covenant “world” was already passing away, and the Church—in Christ—was the prophesied new creation. This process would reach its culmination at Christ’s coming, which Paul believed was near (1 Cor. 1:7–8; 10:11).

Paul’s Use of Isaiah 66 in Thessalonians

Most commentators and Bible cross reference works will make it clear that Paul in 2 Thessalonians 1:7–8 is quoting or alluding to Isaiah 66:15:

“This is evidence of the righteous judgment of God … when the Lord Jesus is revealed from heaven with his mighty angels in flaming fire, inflicting vengeance on those who do not know God…” (2 Thess. 1:5–8).

“For behold, the Lord will come in fire and his chariots like the whirlwind … by fire will the Lord enter into judgment … and those slain by the Lord shall be many” (Isa. 66:15–16).

Neither Isaiah nor Paul is predicting the end of the physical world. In Isaiah 66, there are survivors of the Lord’s coming—who go on to declare His glory among the nations (Isa. 66:19). Paul echoes this, promising relief to the persecuted Thessalonians and judgment upon their first-century Jewish oppressors (2 Thess. 1:5–10). This makes perfect sense within the historical framework of AD 30–70, when one covenant order (old Israel) was persecuting another (new Israel), and the former was passing away while the latter was being vindicated.

Concluding Isaiah and Matthew 24:30-31 and 1 Thessalonians 4:15–17

Since Jesus came to fulfill “all” the Law and Prophets in His “generation” (Luke 21:22-32) and Paul claimed in his defense that he taught nothing beyond what was written in the Law and the Prophets (Acts 26:22-23), it is essential to examine how Jesus and Paul’s eschatology aligns with Isaiah’s. In Matthew 24:30-31ff., and 1 Thessalonians 4:15–17, Jesus and Paul—addresses (1) the coming of the Lord, (2) the resurrection, (3) the second exodus, and (4) the messianic wedding motif. Each of these themes echoes Isaiah’s eschatological vision, fulfilled in the first century.

Isaiah linked the “trumpet,” “gathering,” resurrection, and wedding feast to the coming of the Lord—a time when Jerusalem and her altars would become rubble. Jesus affirms this in Matthew 24–25, placing these events within His generation, just as Paul does in 1 Thessalonians 4.

We also traced Isaiah 60–66, where the Lord’s coming signals the end of the old covenant heavens and earth and the birth of a new covenant “nation” and creation. Many scholars agree that 1 Thessalonians 4:15–17 refers to this same consummative coming. When compared with 2 Peter 3, it becomes clear that this prophecy speaks not of the end of the physical world, but of covenantal transformation, expressed through symbolic, apocalyptic language.

If Isaiah and Peter describe the same event Paul does—and if they use symbolic imagery—then Jesus’ trumpet “gathering” and Paul’s “rapture” or “catching away” language should likewise be understood apocalyptically, not literally.

“Before we begin our series on the eschatology of our Lord in Matthew 23–25 or Paul’s letters to the Thessalonians, it is essential to first examine one final Old Testament prophetic text—the foundational glue that binds together the eschatology of Isaiah, Daniel, Jesus, and Paul. That text is Moses’ prophetic vision in Deuteronomy 31:29–32:43, commonly known as the Song of Moses.”

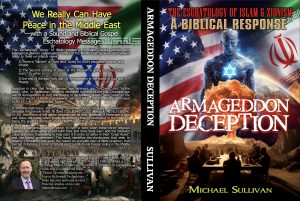

Books by Michael Sullivan: https://fullpreterism.com/product-category/books/

Website: fullpreterism.com

Patreon.com/MikeJSullivan

YouTube teaching videos: @michaelsullivan6868

X: @Preteristesch

[1] Jerome Smith, The New Treasury of Scripture Knowledge: Revised and Expanded (Nashville: Thomas Nelson Publishers, 1992), 802.

[2] John Lightfoot, A Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, vol. 2 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1859), 319.

[3] Adam Clarke, Clark’s Commentary on the Bible, accessed Feb 23, 2025, https://www.stepbible.org/?q=version=Clarke@reference=Deu.32.

[4] John Gill, Gill’s Exposition of the Entire Bible, commentary on Deuteronomy 32:22, accessed Mar 29, 2025. https://www.studylight.org/commentaries/eng/geb/deuteronomy-32.html#verse-22.

[5] Ernest Martin, The Seven Hills of Jerusalem (Portland, OR: Associates for Scriptural Knowledge, 2000).

[6] Douglas Wilson, When the Man Comes Around: A Commentary on the Book of Revelation, (Moscow, ID: Canon Press, 2019), 245–246. Emphasis added.

[7] John Owen, “Providential Changes, An Argument for Universal Holiness,” in The Works of John Owen, ed. William H. Goold, vol. 9 (Edinburgh: Johnstone and Hunter, 1851; repr., London: Banner of Truth Trust, 1965), 134–135.

[8] Ibid., 138.

[9] Ibid., 139.

[10] John Lightfoot, Commentary on the New Testament from the Talmud and Hebraica, vol. 2 (Peabody, MA: Hendrickson, 2003), 318–319; vol. 3, 452–453. Emphasis added.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Ibid. Emphasis added.

[14] John Bray, Matthew 24 Fulfilled, 2nd ed. (Powder Springs, GA: American Vision, 1999), 136.

[15] Adam Clarke, Online Commentary on the Bible, commentary on Matthew 24:29, 137.

[16] John Owen, The Works of John Owen, Volume 9: An Exposition of the Epistle to the Hebrews, ed. William H. Goold (Edinburgh: Banner of Truth Trust, 1965), 134.

[17] Bray, Matthew 24 Fulfilled, 125.

[18] G.K. Beale, The Temple and the Church’s Mission A biblical theology of the dwelling place of God, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 2004), 25. Emphasis added.

[19] Crispin H.T. Fletcher-Louis a contributing author in, ESCHATOLOGY in Bible & Theology Evangelical Essays at the Dawn of a New Millennium, (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1997), 157. Emphasis added.

[20] J.V. Fesko, Last things first Unlocking Genesis 1–3 with the Christ of Eschatology, (Scotland: Mentor, 2007), 70.

[21] John Brown, Discourses and Sayings of Our Lord (Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust, 1990 [1852]), 1:170.